Lynda Gammon

Lynda explores the theme of “space/place” using sculptural installations or ‘wall works’ and photography.

Gammon Meditating 25 minutes 562 Fisgard, 4” x 5” analogue contact print photograph, 2015

Biography

Lynda Gammon (b.1949) grew up in Vancouver, BC where as a young adult she engaged with arts and artists at her mother’s craft supply store and gallery, Handcraft House, as a teacher of weaving and spinning classes. Gammon studied at The University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University during a time distinctly influenced by the 1960s and 1970s counter culture movement. She took courses in many departments including visual arts, English, political science, and future studies eventually graduating from SFU with a B.A. in English. At the encouragement of her professor, Wendy Dobereiner, she moved to Toronto to pursue a master’s degree at York University [M.F.A. 1983]. Following her M.F.A. she was offered a position at the University of Victoria where she is currently a Professor Emeritus.

Lynda Gammon’s artistic work of the last decade has focused on “space/place,” a theme she explores using sculptural installations or ‘wall works’ and photography. Her work considers representations of illusionistic space in photography and the dimensional, physical space of sculpture. Her work often brings together architectural materials and forms and artistic materials and forms to comment on representations of place. Her work also reflects on ideas of memory, particularly the memories and stories of spaces and the relationship between photographic representations and what the mind recalls or imagines.

Alongside her artistic work Gammon is committed to working with other artists in collaborative and curatorial positions. In 2004 Gammon created flask, a small art and artists book publishing group. Each book is the result of a unique collaboration between Lynda and another artist. Gammon also sits on the board of Open Space Gallery where she has curated WorkPLACE (2014) and co-curated Realities Follies (2015) with Wendy Welch.

Selected Excerpts

Lynda Gammon on how her art begins

Lynda Gammon on history, memory, and her studio wall

Lynda Gammon on community in Chinatown

In Conversation with Lynda Gammon

Full Interview

Full Interview Transcription

Edited and Transcribed by Nellie Lamb in consultation with Lynda Gammon

Text in square brackets indicates additions or subtractions from original interview as recorded in the audio file above.

NL: I’m here, Nellie Lamb, talking with the artist Lynda Gammon on February 5th, 2016 for the PNW-WAOHI and we are here in her studio at 562 Fisgard St. in Victoria’s Chinatown to talk about her art work, her other related projects, and her experiences working as an artist in Victoria. So I thought I’d start by asking where you’re from.

LG: Originally from…I was born in Port Alberni actually on the island here… and we quickly moved to Vancouver when I was one and a half and we lived there until I was around 30 and then I went to grad school in Toronto and then I moved here to take the job at UVic and I guess that was around 1983 and I’ve been here ever since.

[NL: Can you tell me about early artistic influences?

LG: When I was about fifteen or sixteen my mother began Handcraft House, a craft school, a store for craft supplies and a craft gallery in North Vancouver. It was a real hub for the counter culture movement with long-haired hippies, (many recent draft dodgers from the U.S.) doing pottery, glass blowing, weaving and spinning etc. Crafts were very much a part of the 60’s and 70’s counter culture movement in Vancouver. Evelyn Roth taught classes there and Wayne Ngan had one of his first pottery exhibitions there, as did Mick Henry. It was a totally amazing place. I worked there and taught classes in weaving and spinning etc. during my late teens and 20’s.]

NL: Excellent! What was it like… What brought you to Toronto because you went to Toronto to York, right?

LG: Yeah I went there to go to grad school. I’d been at Simon Fraser. I did an undergrad degree in English really. At that time it was in the ‘70s and I think the university systems were a bit different but I was taking all kinds of courses there [visual arts from Ian Baxter, anthropology, political science philosophy, English, future studies etc.] and I was also taking courses at UBC in the art department [from Michael de Courcy, David Rimmer, Roy Kyooka, Wendy Dobereiner etc.] and then in the end I was able to pull things together to get a degree from Simon Fraser in English. And then I applied to York to go to grad school and that was what took me to Toronto.

NL: Is that when you decided to be an artist? When you applied to grad school in Toronto?

LG: No because I went to grad school when I was thirty and I was already working as an artist already. I think I already thought I was an artist. [Laughter]

NL: Well I’m sure in some ways you absolutely were!

LG: By then I was 30 or so…

NL: Yeah

LG: Yeah so I didn’t… I’d always been, I think I’d always been making art. And certainly I was making art at UBC with Michael de Courcy, [David Rimmer, Roy Kyooka and Wendy Dobreiner etc.] was there at that time and various other artists it was an interesting time in Vancouver, [a time which saw the beginning of INTERMEDIA] and some of the early sort of photo and performance [works] and just the beginning of artist run spaces at that time. So it was an interesting time as I remember it.

[NL: Can you describe what the Vancouver art scene was like in the ‘70s? What was interesting about it?

LG: Well the backdrop for the art scene was the counter culture movement. We truly believed we could build what we saw as democratic alternatives. For example while I was at S.F.U. there was such turbulence in terms of demonstrations that students occupied the president’s offices, the faculty club and in the end shut down classes altogether with lectures and ‘sit ins’. We actually lost a whole semester! Hard to imagine that happening now… but it was very exciting for me at the time. I was there recently and one of the younger students I was talking to at the gallery said, “Oh you were part of the radical generation!”

In terms of art production we felt there was a new freedom. For the courses I took from Ian Baxter we were asked to actually paint on the models, we made art out in the woods behind S.F.U. I was completely enthralled with this highly conceptual approach. It was not like anything I had ever seen or thought about in terms of art making at the time! I think the course started with twenty or students but in the end it was only me and one other guy.

With Michael de Courcy at U.B.C. we didn’t actually have any courses but met for breakfast and hung out downtown taking photographs. Then we would come back to the studios and develop and print in the darkrooms (in ‘the huts’) throw all of our photographs onto the floor and walk around looking at them for our discussion and critiques. I remember being very excited to hear Tom Burrows speak of his recent trip to the Netherlands to look at squatter’s residences. We gave ourselves our own grades and there was a complete disrespect for what we saw as the bureaucratic systems of the university. This all ended abruptly when U.B.C. decided to ‘clean things up,’ did not re-hire Michale de Coucy, and hired a Chair for the department recently arrived from England who immediately locked the darkroom and declared that “photography was not an art form” that must have been the mid to late ’70s at that point.

That disrespect for the bureaucratic systems was also taking place in the traditional art galleries and museums where galleries that sold works were seen as outdated and the museums were seen as not meeting the needs of a new generation of artists who were involved in performance, video and other forms of new media. This spawned the beginning of the artist run centres and INTERMEDIA and the Western Front and Pump funded by the Canada Council and became the important venues for us.]

NL: Was there anyone there who you worked with who really, I don’t know, shaped your thinking or your practice?

LG: Yeah well I think Roy Kiyooka, photo and I think Michael de Courcy to quite a large degree and then I worked also with Wendy Dobereiner I don’t know you might not know…

NL: I’m not familiar.

LG: I worked with her and she was very encouraging about going onto grad school so that was yeah… yeah.

[Wendy arrived after Michael, Roy Kyooka and many of the ‘guys’ had left. It was wonderful to see a young woman artist (and she was flamboyant and gorgeous). She had just graduated from York University with an M.F.A. I had not really considered going to graduate school but Wendy said “Lynda, you must.” When I got accepted she was incredibly encouraging once again. Wendy taught in a more traditional manner. I mean we actually had classes and critiques and learned techniques. At this point I shifted from a more photo-based practice to printmaking, as this was Wendy’s area of expertise.]

NL: Excellent. And so moving from your educators to your role as an educator how has that shaped your work and your art?

LG: Oh gosh that’s a really big question isn’t it, eh? [Laughter] role as an educator shaped… well I think… a large part of the shaping it think comes through the context in a way because you when I [first] came here in [1983] […]I wasn’t just teaching but I became a part of a faculty of other instructors so when I came here I met some very amazing artists, [Roland Brener], Mowry Baden and Fred Douglas – your father and I was working in the area of photography so Fred was very influential at the time, and Pat Martin Bates was here as well and let me think… yeah so anyways I part of a context of artists who were working here. And Elspeth Pratt and I came at the same time so we actually shared this studio for a while that we are in now, 562 Fisgard [and Roland Brener was next door and Fred Douglas was next to Roland.] So I was a part of a […][group of] artists so I think that shaped my context after coming from grad school to a large degree.

And then working with students they’re always giving you amazing ideas and still to this day I mean just art is always moving it’s always changing. Contemporary art is always changing, new ideas and new ways of making things new ways of making things, of thinking of things. So that context is incredible to have, it’s such a gift to be able to be a part of that community because Victoria is quite a small… It’s a small artistic community so that kind of puts you in touch with the larger world.

And then more recently, (that was when I first came), after that Robert Youds and Daniel Laskarin and Vikky Alexander, Sandra Meigs and I hate to list people without remembering everybody’s names but everybody all of the people at UVic have been a huge influence. [Lucy Pullen and Luanne Martineau were very important colleagues for me.]

[In addition I would have to say that the privilege of being involved as a faculty member at the university has to some extent allowed me to maintain a studio and studio practice, to exhibit and travel. So it is a very great gift in a way.]

NL: Have you seen the, you mentioned how small the Victoria art scene is… Have you seen it change over the last 20 years, 30 years?

LG: I don’t think a whole lot in a way. I think surprisingly not so much… yeah it’s still small [laughter] let me put it that way. It’s a little bit cliquey I think like there’s sort of groups of artists in different areas doing different things. But I’m on the board at Open Space now and I notice like it seems like its kind of a separate entity from the UVic sort of context, there’s overlap of course but I think there remains quite a bit of separation.

NL: Do you think it’s important… Is there work to do bridging those gaps?

LG: Yes. I think there is work to do. I think there could be more synergy. I think we could do more if we did more together. So its kind of a I don’t know… Victoria is kind of funny town in terms of its culture and it’s art culture. I always thought it was going to get going in some way but I can’t really say that it has, from my perspective. [In terms of the relationship between the faculty and the community], I think people, certain people on the faculty, tend to travel to exhibit, they travel elsewhere, and a lot of people [in Victoria] don’t necessarily even see their work. And they’re working in their studios which we are kind of apart from. So you know there may be some changes I know Sandra Meigs is having a show at the Winchester opening I think tomorrow so that’s a good thing…. And she had a show at Open Space last year so that’s great. [Other faculty members have shown here for sure…] And there are some opportunities but I think a lot of people don’t know what other people are doing still.

NL: Yeah I wonder… I feel like the Vancouver art scene has changed in a huge way.

LG: Yes.

NL: And I wonder if Victoria is going to kind of I don’t know follow suit or if it is going to retain some sort of autonomy.

LG: I’ve wondered that myself because you know the Vancouver scene is has so many smaller galleries with younger artists showing now and it isn’t just the more established core. It does seem to have really changed and definitely for the better. And also there’s some you really sort of major players, the Equinox that area down there, there’s different areas of galleries it’s really changed. But I don’t know that there’s… I mean yeah there is some smaller galleries here but are there more than there were you know ten years ago? I’m not so sure that there really are.

NL: Yeah, I mean some of them have lasted a long time, which is really…

LG: Yeah that’s amazing, Xchanges has been a long time, Open Space has been a long time and that part is quite great. [I’m on the Board of Open Space and they work very hard in the community for sure.]

NL: I guess it’s about growing from that.

LG: Yeah it’s time. [Laughter]

NL: I also wanted to talk about your art, of course, and I thought I’d start by asking what about your art is most interesting to you.

LG: Oh wow.

NL: [laughter]… or just interesting it doesn’t have to be most interesting.

LG: Well I think all of my work always begins with photography. […] Looking back it seems to always have started with taking photographs of a space or a place and that place or space seems to have often, almost always, been a space that I work in as a studio. […] So I’ll start and take photographs of this space say (and a lot of photographs of this space) and then I took photographs of a place where I had a studio at Xchanges and I took pictures in Herald St. and then I had a studio in Rotterdam for a while took a lot of pictures there. So it almost always starts with I guess you could call somewhat documentary photographs of a space. So I don’t know if it’s so much about what interests me most about my work but it’s just what you… I suppose just what you gravitate to and what you end up doing ends up being the thing that interests you. I think that then I take the photographs and then almost always I do something with the photographs I manipulate them in some way often into sculptural installation as you’ve seen. And I think that process, the process of taking the photograph and doing things with it, cutting, folding, gluing, collaging, enlarging all of those things are a way of often trying to get to a sense of the space, maybe a feeling about the space, or you know, memories of a place, thoughts about a place all kinds of things that photography maybe doesn’t do that well. Like for instance with this piece you know we are taking photographs with this large camera, this 16×20 camera. Trudi [Lynn Smith] and I have been working together to photograph the studio wall in minute detail, so it’s a 16×20 camera taking a 16×20 image of the studio wall and so when you get that photograph done it’s a very detailed 16×20 photograph of the wall. But I’ve also been sitting and meditating and looking at the wall for the same length of time as the exposure so it’s a 25 minute exposure and then I sit and I meditate on the wall for 25 minutes and while I’m meditating on the wall I’m thinking about all kinds of things, like about the way that this used to be a rooming house for Chinese migrant workers and I think about the fact that you know Roland [Brener] used to be next door and your father [Fred Douglas] was on the other side and I think about a lot of things, you know, things come into my head, lets put it that way. I guess not so much thinking about it because meditating is more just allowing the thoughts come and go. But the thoughts that come and go are memories and they’re also imaginations of what it was like for a Chinese migrant worker to live here they are also based on sort of gossip that I hear about there being a leper colony here and I wonder if any of those people lived here and all kinds of things that come up in your mind that the photograph clearly doesn’t capture. So I’m kind of interested in those things. There’s the photograph and then there’s the things it doesn’t capture so I’m often involved with trying to somehow imbue the photograph with feelings and thoughts about the space that might not be there. Does that make sense?

Gammon Meditating 25 minutes 562 Fisgard, 4” x 5” analogue contact print photograph, 2015.

NL: Yeah that’s really interesting. I when I was thinking of your work this part of … have you ever read Cat’s Eye by Margaret Atwood?

LG: Yes, yes.

NL: In the very beginning she says… I wrote it down… “I began to think of time as having a shape, something you could see, like a series of liquid transparencies, one laid on top of another. You don’t look along time but down through it, like water. Sometimes this comes to the surface, sometimes that, sometimes nothing. Nothing goes away.”

LG: Uh-huh…

NL: I don’t know that sort of…

LG: That’s so great!

NL: Especially the part about liquid transparencies there’s something almost photographic about that…

LG: Yes there is. And also I think for this particular project [1:1 (25 minutes) 562 Fisgard] […] we were really thinking about that with the… well also that piece that I did called… the more recent piece Studio Wall Fragments thinking about that kind of thing taking pictures of the wall but then layering them one on top of another because history is.. that kind of history and memory, it’s kind of liquid it’s not like we think of history as being like this happened then that happened then that happened… it’s more like this happened and then at the same time that was happening and then when did that happen? That was a big memory and that was a small thing that happened so you know history is much more fluid and liquid I think. I really agree. And in this project too it was reiterated because we were thinking about… for this project we wanted to peel back the layers of the wall when I first came to this studio all I could think about was painting it white and making it like an artist studio. Right? And so I did that.

Studio Wall Fragment #6, 7.5’w X 8’h X 18”, digital photographs, foam core, wood, paint, 2013.

NL: Yeah.

LG: But you know later coming back to it I realized how significant the history of this building was and still is. So we are doing this thing where we are peeling back the layers of this wall when you think about peeling layers you think “I’m going to peel off the white layer and then I’m going to peel off the newspaper layer then I’m going to peel off the other layer then I’m going to get to the wallpaper layer” but actually when you are peeling it comes of in chunks and that seems to sort of again suggest that thing of well… how does history happen? It comes off in chunks and it’s messy and there’s little bits and pieces you know it’s not really it’s not just layer by layer or minute by minute in that sense it’s like there’s chunks… then there’s things you pick up again and you look at them and go “oh yeah…” this piece of newspaper that’s talking about selling a farm you know it’s… I think history and memories are like that. It’s a really interesting quote, of course I don’t remember it, but it’s nice.

NL: Yeah I mean you spoke about photography having … it captures something but of course not everything, not the things that you’re thinking about.

LG: Yes. Well it might… but yeah.

NL: It could.

LG: It could. For me I seem to want to imbue it with something more, yeah.

NL: Yeah but I wonder about books and archival material for you, do they have the same sort of capacity as photography or a different but related…?

LG: I think archives are similar. Probably books are too. I always think of my photographs as being a personal archive of course and I always find when I’m, you know, taking things out of my archive that it probably […] mirrors my ideas about historical archives and the way that you can pull a thing out the archive and you can pull another thing out of the archive and you can put them together and you as the person pulling them out create a certain kind of meaning because you’re pulling them out, you’re putting them together. You’re making them have some kind of meaning and I think I’m interested in the idea of archives a lot and it’s sort of hard because you don’t know how much to go into. [Laughter] I mean I’m interested in archives quite a lot and I’m interested in the stuff that’s un-archived that doesn’t go into the archives that doesn’t get there and I think of that project and I think of this project as being quite a bit about that because there is quite a bit of archival material on the outside of this building for instance. There are pictures in the BC archives because it was designed by… I think a British architect John Teague for the Chinese Benevolent Society but there’s nothing, there’s one picture I think about the next door that was a shrine room. There’s the odd little picture about what went on in these rooms. If they were for migrant workers, you know there’s just some word of mouth stories but nothing in the archive about what went on the inside of the building in terms of that history but people talk about it and have ideas about it and they gossip about it and have ideas about what it might have been. But of course it wasn’t in the archives because it was you know the Chinese were marginalized of course as a race or they were seen as unimportant they were on the margins and then I think that its interesting that all of these artists have been in here and it remains in a sense like the work that I might produce that goes into a gallery it would go into an archive but just the activity the day to day all of those things that your father [Fred Douglas] produced, the amazing things that I remember him just throwing in the garbage or under the door you know just all of that stuff that wasn’t actually shown that doesn’t become part of the archive. But I have a piece at home that I grabbed from him that I now have framed on my living room wall. But what about all those things? Nobody knows about that it’s not archives but it’s not unimportant it’s incredibly significant. I think it’s interesting that it remains a kind of marginal furtive space up here. I see it like that. These people are working away in here but nobody really knows and nobody really knows what goes on up here there’s curiosity but also distance we don’t know what artists do, we are a little unsure about what their purpose is. Unless it is sort of framed and goes into a gallery it’s not in the archives.

NL: Sure yeah.

LG: So I think that archives are interesting to me and I think that I work a lot form my own personal archive so archives are interesting in that way. I build a personal archive with photographs that I then retrieve and put together in different ways… but then the idea of archive interests me in a larger…

NL: …the personal.

LG: And the historic museum and institutions and what their relationships to archives are what’s gathered what’s missed I’m pretty interested in what happens in the margins.

NL: Yeah.

LG: Yeah.

NL: Yeah I like the I mean… I don’t know if I can say that I like the idea of the sort of secrecy or…

LG: Yeah I called it like furtiveness almost.

NL: Yeah.

LG: It’s sort of … it’s not because people… it’s not because it’s secret or private it’s just I don’t know there’s no real way for it to be public.

NL: Yeah. What are you going to do with it?

LG: There’s no avenue. Yeah, what are you going to do with it? There’s not sort of avenue although people are totally fascinated when they do come up here. They’re like “all this stuff is going on up here!” It’s not that they are uninterested. There’s an avenue for the completed work because that goes to the institution, but for the mucking around in the studio there’s not that much opportunity. Hence my interest in the studio pictures. The kind of furtiveness of the early 1980s pictures where there’s some kind of half finished sculptural thing on the wall. But the subject matter of the work is not the sculpture. Its… the work is not the sculpture its barely of the place it has a very furtive quality about it and that remains of interest. Cold in here isn’t it?

NL: Yeah getting cold now, finally.

Both: [Laughter]

NL: With the …because you combine photography and sculpture and of course other media as well, I wonder how that initial… was there a moment where you thought “Ok well I should probably bring sculpture into this and it’ll add… it’ll add something for me’’?

LG: It probably came from a few places one thing was that when I was younger in Vancouver there was a lot of… with Roy Kiyooka there was a lot of interest in photographic collage for one thing. For another thing, it was a time when photographs were not treated as precious as they have been, like for our critiques we would just throw our photographs on the floor and we would just walk around and talk about them as they were on the floor I think there was a sense of that. I think also photography for me, as it was for your father, is very tactile because it was all done in the dark room with chemicals so there is a physical quality (which is of course very different now.) It’s the way that photographic paper looks when it comes out of the developer, the way that you know different kinds of paper, how floppy the rag paper is as opposed to the RC paper you know how it feels and all that tactile aspect of making work in the dark room. […] And I think the collage and assemblage from the Vancouver period I think that artists were beginning to experiment with that at that time with actually using photographs in sculptural forms in Vancouver and in California and other places. That was all of interest and then when I came here I had Roland [Brener] next door and Mowry [Baden] of course was a strong influence and then Elspeth Pratt also, a sculptor, I was sharing a studio with her. But I was already doing sculptural things at York so I guess… but not so much sculptural photos when I was at York so I think that’s when the more sculptural photo stuff started to come in… so I was making sort of wall assemblages and I was making photographs and then they started to actually come together.

NL: Right.

LG: They moved from just being sort of collage, flat collage works, to being more three-dimensional collage works… I don’t think they even now are sculptural because they always relate to the wall. They’re actually basically wall works so they’re relief works or assemblages. I still feel a little uncomfortable about things that are completely sculptural. And they’re ephemeral too. I think a photograph is a rather ephemeral material to make sculptural out of. Yes. Does that answer? Did I veer off on some tangents … is that ok?

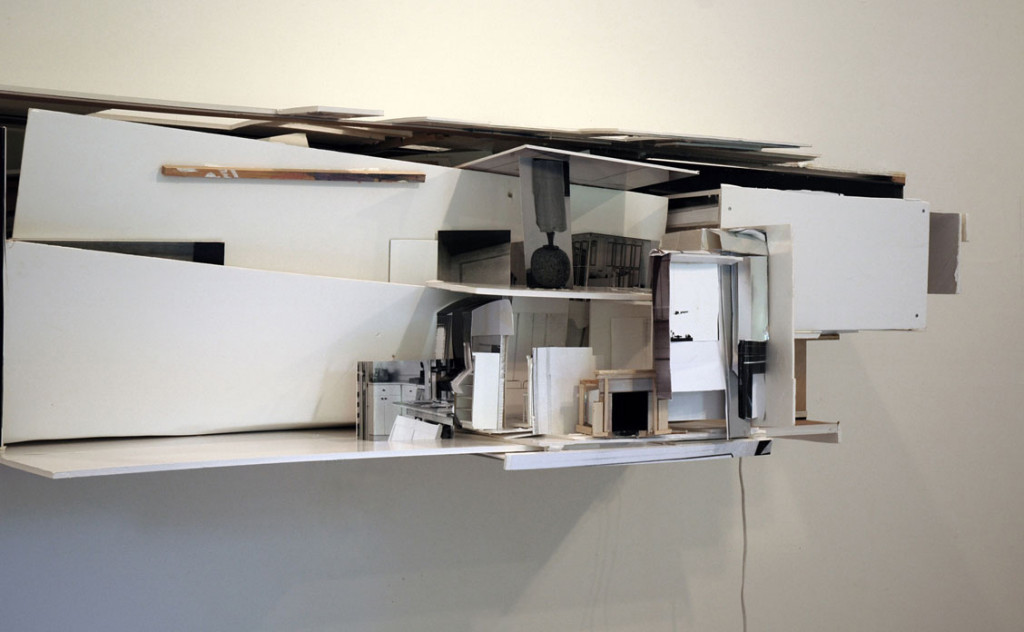

Salvaged # 11, 144” X 56” X 54”, paper, cardboard, foam core, photographs, wood, electric lamp, 2006.

Both: [laughter]

NL: That’s great. I think the idea of space is really captured in the making the collage three-dimensional with the photographs.

LG: So real space, illusionistic space that interests me a lot.

NL: Uh huh and yeah and those two things sort of come together and there’s a new or an interesting understanding about the way space is and the way space can be thought about.

LG: Yes. Definitely I am totally interested in that. And that has always captured my interest. Partly because of the way that a photograph supposedly… it does supposedly capture or photograph real space like you look into it and there’s kind of an illusionistic space but that’s not really real space because it’s not physically real. Yeah my interest in that sort of area between those things is… yeah. Those works that I did the works called Salvaged they were architectural models, large architecture models, that were made from photographs of architectural interiors so you could look at a photographic part and they were actually deliberately hung at a photographic height so you could look at them and you could look into the photographic illusionistic space but then you could also you could also look into the model space. There’s different kinds of space operating and that interests me for some reason.

NL: Do your works… do they often come… do you find a material and this will be interesting to add into this project or do you have an idea that then you know that you need to go get that material. Especially for the sculptural works the wall works…

LG: I think that they’re for the most part… well let me think… so for the Salvaged pieces they were mostly photographs mounted on foam core or on mat board so […] it really refers to artistic practice it’s like a material that you would normally mount a photograph on. So that’s kind of a part of that canon and then I would combine that with 2x4s and screws and plywood and shelf hangers and things that would be more related to home building. The home building canon. So in that case it would be trying to think about well… real houses are built with these things but photographs use these materials. So photographs use these materials and homes use these other materials so in that case it was bringing those two things together. Quite a lot of the works are pretty much just photographs and thinking of ways to hang them. The wall fragments Studio Wall Fragments. They were mounted on foam core. Often really thick layers of foam core […] very much related to what to what photographs would be mounted on i.e. on foam core. Some people have said “You know you could mount these on Dibond they’d be a lot stronger…” but I’m interested in more the sort of … the history of collage and the kind of ephemerality so I think something that I can kind of cut and paste myself and paste my self something that has a that’s more ephemeral would always be of more interest to me as opposed to something that has a kind of forever rigidity. So the lightness and fragility and ephemerality.

NL: And assembling and disassembling…

LG: Yes easy to take apart and you can put it in a crate easily and it’s easy to ship. Those big Salvaged pieces, the big wall mounted sort of model things, although they don’t look that big in the picture they are like 12 feet. 12 feet wide, so quite big. I would make them in the studio and then I would take a photograph of them and then I would draw a line around the outside of it on the wall and then I would take it down in pieces and number the pieces and put them into the crate and go […] to the gallery and [install] them. […] In the photographs they have a finished look but in actuality they are very raw. They are just kind of taped and things are all kind of jammed together. […] But actually […] they’re somewhat deceptive,[…] they’re quite carefully constructed in the studio and then reconstructed in the gallery I think that there’s an aspect of the formal properties of the piece as a collage that are important to me.

NL: I also wanted to talk about your publishing work.

LG: Oh yes.

NL: flask and how that started.

LG: Yeah. That was you know working as an artist in the studio is kind of lonely although my life isn’t lonely because I’m teaching and I have so many people in my life but I think that the actual making of things I have felt like I was always making things by myself and it would be interesting to work or collaborate with another artist in a certain way. So I thought that I would start flask, which is an artist book press. I thought when I first did that I was casting around thinking there’s so many amazing opportunities now to make books through instant publishing that was the beginning of that sort of thing. I thought that would be so great. I could do that kind of thing and but then it somehow didn’t end up being that [laughter] it ended up being these really hand made books that really take a lot of work to make each one so they ended up being that so that’s just kind of where it’s gone. The first book that I did was with Luanne Martineau which you’ve probably seen on the website. What happened was, I invited artists who had… I wasn’t looking for artists that make books I was looking for an artist I was interested in their work that I could then make a book with. So I had made some books myself. And your father had made some books and actually he was influential in that area of artist books and the idea of making books and he did some amazing things that way. […] Anyway that was a huge inspiration so then I made a book with Luanne to begin with and so she had ideas and then I had my printer at home so I basically printed all the pages myself and yeah it sort of went from there. And I’m still doing it. It’s a kind of occasional thing. [I have to find] somebody I know that I want to work with. So I worked with Luanne that was really great and then Vikky [Alexander] and Chris Miller and more recently Trudi [Lynn Smith] and I did a work together, which is actually here.

NL: Oh yeah?

LG: And who else? Yeah so it’s been Anne Steves who was a student of mine I made a book with her in conjunction with Open Space together recently that was one of the very recent ones and yeah I still have some ideas for other ones, other artists that I want to work with so yeah… yeah.

NL: Yeah yeah that’s really exciting.

LG: It’s fun

NL: … collaboration I think is really special.

LG: Yeah exactly and I think that has maybe led me to… because lately I’ve been doing all kinds of collaborative projects with Trudi [Lynn Smith] particularly, Smith. And speaking of sort of un-archived or sort of projects under the radar I recently made that website. I have on it the blog section and I thought well that blog section seems to me an opportunity to just publish or just put on the web just some of the other activities that one does, you know? Like Trudi and I went into the darkroom and learned how to make … dry plate photographs and it was really interesting and I did some work with photo-etching and you know many things that I do I like to do things like that and I think they inform the sort of more major work. The things that seem to be on the website under the projects part, they inform the more major work like this project I don’t really know where it’s going to go in terms of this project with the big camera in the studio. We did an event where we invited people down to talk about the piece but for me it still doesn’t seem to be finished as a project that […] would go into the gallery […]. I don’t know what form it’s going to take yet so there’s sort of […] the main projects and the sideline projects under the blog of which I’ve got many more things to add.

NL: [laughter] lots of things going on simultaneously and informing each other it seems and informing each other I assume.

LG: Yes informing each other of course. And the blog is an opportunity to do a little more writing which I was interested in doing a little more of and maybe that came out of doing books and a little curating so I’ve been stepping into…

NL: Right! Yeah at Open Space.

LG: I’m going to do a show with Arnold Koroshegyi and Laura Dutton and I’m just sort of shopping around a little exhibition right now of Nick Vandergugten and Trudi [Lynn] Smith so we have been sending it around to some galleries to see what might stick so doing a little bit of that. Wendy Welsh and I co-curated a painting show at Open Space and then I did that WORKplace show earlier. Yeah so I may branch out. I like to give younger artists an opportunity to or if there’s any way I can help to give younger artists help to get … because it’s such great work and sometimes it hard to get it out there…. Maybe there’s a way I can put together some opportunities.

NL: That’s I don’t know that’s very…

LG: Its good, it’s fun, it’s interesting! Again it’s like collaboration it’s a kind of … it puts me in deep contact with artists and their work. Working with Nic has been great. Emails flying back and forth about his work and how to represent it and he’s working on artist statements and I’m writing bout the show and lots of deep thinking about his work and how to represent it, he’s working about his artists statements there’s an opportunities for some deeper thinking about a piece that I saw and I said a few things but I didn’t really at that time…. You know what I mean you do that.

NL: That’s what excites me so much about curation that time and necessity almost to really really engage with an artists and their work and to think about the best way to present it…

LG: Yes and the best, the interesting combinations of work, like why would this work of Trudi’s be interesting with Nic’s and to try and articulate that.

NL: What can they say separately and what can they say together? What can they say in this space versus that space?

LG: I think the idea for the show just came to me I was just like that work and that work would be so great together but I hadn’t really thought about why… and you start to talk to them more then you get an opportunity to get to know them better. You get to talk to them about what they think of the work. It’s just great, so interesting.

NL: Yeah it’s a luxury

LG: It is a luxury. Yes it is totally. And you have that experience yourself and will have more because you’re young and you’ve got lots of time.

NL: I hope so! That’s the goal!

LG: You […] just need to start doing it, you know, propose a show for the 50/50 because people are always thrilled to have their work shown. Like Wendy Welsh has the Slide Room Gallery. Do you know that space? She said they’re looking for curators to put together shows….

NL: On Quadra [Street]?

LG: On Quadra. They do some interesting little shows and so she said “I don’t know if you’re interested but we are curating a show but I wonder if you’d like to be in it.” I said “oh sure I’m happy to do a piece for it” oh and I contacted Rob Youds and he said he’d like to… and other younger artists and I think you’d be surprised when you actually just decide I’m going to put forward an idea for a show for the Slide Room Gallery. Just ask whomever you want. Ask Sandra Meigs if she’ll be in it and she probably will.

NL: Maybe she’ll say yes.

LG: She probably would… [laughter]

NL: It never hurts to ask. And even if doesn’t happen this time…

LG: And so I think just finding just little spaces like hat because Wendy is looking for curators. Jump in just start doing some things!

NL: I think the only other thing I wanted to ask is if you feel … like the community here, if there is a community here in this one block of Chinatown between you, as an artist and the other artists who have studios here and the shops downstairs?

LG: Right yeah. I really love the community here in Chinatown, I really love it. I think that Chinatown is really special because I think there are different regulations, obviously or we wouldn’t be here. Because it would be oh, not up to fire code and it would cost [$]1000 a month and we wouldn’t be able to afford it and we wouldn’t be here. The other thing you notice is you go downstairs and you, as you notice, there’s boxes of vegetables all over the road and cars are triple parked so there is obviously a difference in regulations in what can happen here. I mean for better or worse. I worried about your father in that space. I’m not saying there shouldn’t be regulations but the fact that there isn’t creates sense of community. That feels… does feel very nice and you know the coffee shops you get to know people a little bit. I must say that I’ve come back here in the last few years only part time… so I’ve just been kind of coming and going… Todd and Keith next door it’s great. It’s not like the community when your father and Roland and Elspeth were here. That was fantastic! But you know things can’t last forever I guess. But that was fantastic that was very special kind of community of art because we were all working at the university and we were all working here. Ultimately we… a dangerous combination. Too much of everybody living out of each other’s pockets. [Laughter] But it was really fantastic while it was really good. So that was a really amazing community and a kind of amazing time. That would be interesting to delve into at some point. Because it was quite remarkable.

[NL: I wonder if we could delve into that community a bit here. Can you tell me about a moment that stands out as an example of what that community was like?

LG: Too many memories to possibly share in so short a space but,

I think it was just that we were all in the studio a lot and all making work and sharing it with each other. Also students used to come by the studio quite a often too, so it became part of the learning and teaching experience.]

NL: Well unless you have anything else you’d like to add…

LG: No no just wishing you all the best with your project and your curating… so next year you’re going to work and start writing and curating all I can say is just go for it. You’re not going to wait too long just jump right in!

NL: Yes yes do it all! Thanks so much.

LG: Terrific that’s great.

-END-

Bibliography

Cormier, Nikki and Sally Frater. “ Everyday Alchemy.” Lynda Gammon – Texts. Accessed February 3, 2016. http://lyndagammon.ca/texts/. Dault, Gary Michael. “Lynda Gammon and Sonya Hanney.” Lynda Gammon – Texts. Accessed February 3, 2016. http://lyndagammon.ca/texts/. Gammon, Lynda. “Bio.” Lynda Gammon – Bio. 2015. Accessed February 03, 2016. http://lyndagammon.ca/bio/. Gammon, Lynda. “Regressive Wandering.” Lynda Gammon – Texts. Accessed February 3, 2016. http://lyndagammon.ca/texts/. Gammon, Lynda. “Salvaged.” Lynda Gammon – Texts. Accessed February 3, 2016. http://lyndagammon.ca/texts/. Gammon, Lynda. “Studio Wall Fragments.” Lynda Gammon – Texts. Accessed February 3, 2016. http://lyndagammon.ca/texts/.

McCormick. “Rearrangements; Sculpture/Performance/Photography.” Lynda Gammon – Texts. Accessed February 3, 2016. http://lyndagammon.ca/texts/. Pakasaar, Helga. “Lynda Gammon’s Portraits, 2003.” Lynda Gammon – Texts. Accessed February 3, 2016. http://lyndagammon.ca/texts/. “Recently Constructed Works.” Mercer Union. 1990. Accessed February 03, 2016. http://www.mercerunion.org/exhibitions/recently-constructed-works/. Ritters, Kathleen. “Notes on Precarity – Essay for ‘Silent as Glue’ Catalogue.” Lynda Gammon – Texts. Accessed February 3, 2016. http://lyndagammon.ca/texts/. Smith, Colin. “Residual.” Lynda Gammon – Texts. Accessed February 3, 2016. http://lyndagammon.ca/texts/. Smith, Trudi Lynn. “Stride Exhibition Essay.” Stride Gallery. 2008. Accessed February 03, 2016. http://www.stride.ab.ca/arc/archive_2008/lynda_gammon_main/lynda_gammon.htm.